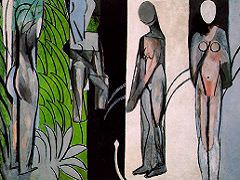

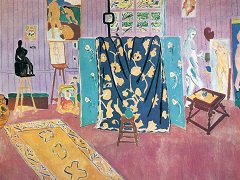

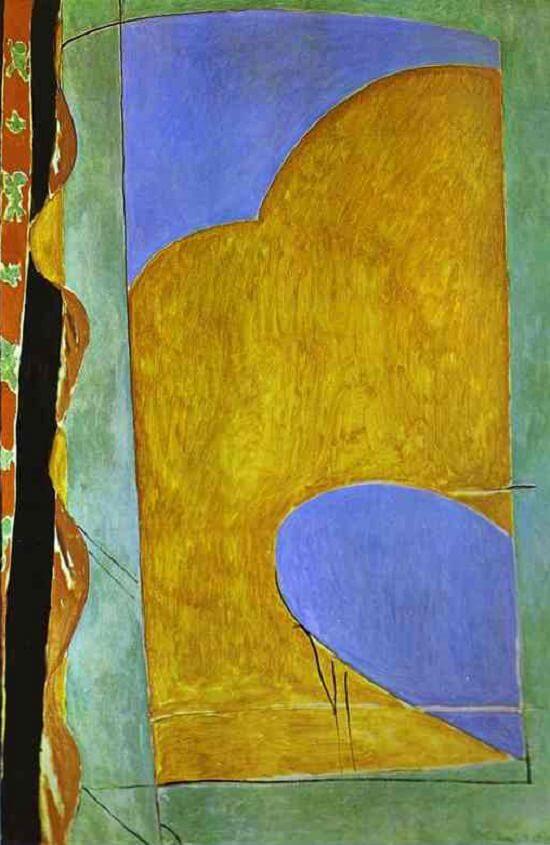

Composition: The Yellow Curtain, 1914 by Henri Matisse

One of the climactic instances of Matisse's treatment of the view through an open window, the present picture presents a daringly abstract landscape and frame which are contrasted with the relatively realistic handling of the curtain at the left. The green areas of the architectural border are so flatly treated that the landscape beyond is almost literally a picture within a picture and might even be read as a boldly simplified painting hanging on a studio wall. The curtain is actually red with a green floral pattern, and its reverse side, yellow, is seen only in two places where it has fluttered back into the room as the result of a breeze. Its yellow is nearly identical to the yellow-ocher ground of the landscape, a broad, flatly painted area which vibrates against two areas of relatively pale blue, the sky at the top and the elliptical form at the bottom, an area that might also be read as the pool of a small garden.

In abstract juxtapositions of flat colors such as these the artist foreshadows at an early date the effects of the papiers-decoupes that will crown his oeuvre in the 1950s. Notable is the freedom with which he treats the rectilinear contours of the window, producing, in effect, an unreal arch at the top. Such minor adjustments and dislocations serve to comment upon the rigidity of the picture frame, which is softened chiefly by the curving folds of the curtain, a feature that is itself held in check by the bold black strip that adjoins the picture frame only at the composition's base. While Matisse, like most of the Cubists, would never pass beyond the rendering of the world of appearances, he here touches a degree of abstraction that will not recur in his art until the monumental Snail. In creating these masterpieces of representational understatement the artist does not seem to be posing a visual riddle, as is so often the case with Cubism and its aftermath. Rather, his statement is an unambiguous praise of color in its multitude of possible combinations. The viewer is drawn into a state of relaxation and euphoria through the means of the hues themselves, although a tenuous contact is maintained with the world of everyday, secular perception. In contrast with the intellectual challenge and mental tension provoked by such pictures as Goldfish, with their Cubist conundrums, the present picture is a model of decorative and compositional clarity.