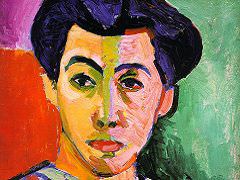

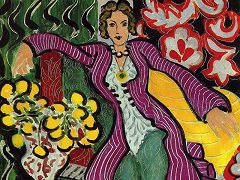

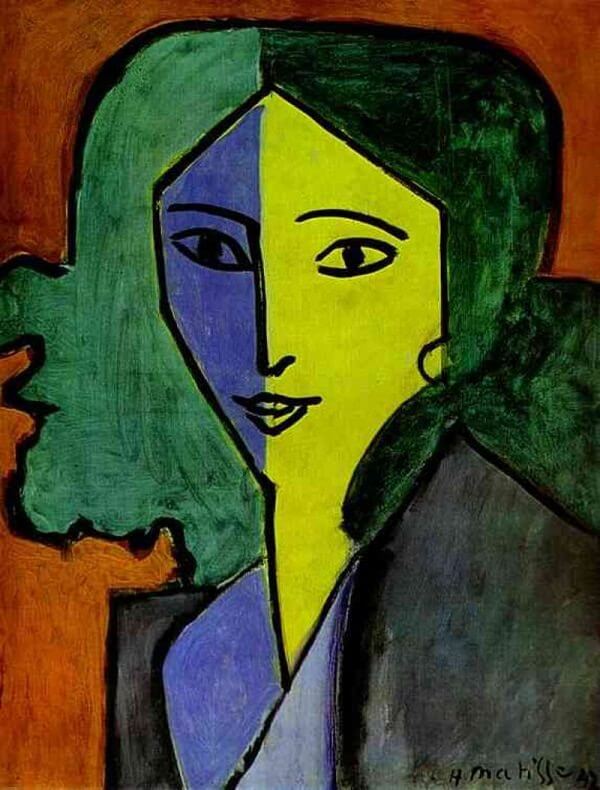

Portrait of Lydia Delectorskaya, 1947 by Henri Matisse

Lydia Delectorskaya was born in 1910, the only child of a doctor (whom she adored), Lydia had been orphaned and forced to flee Russia in the turmoil after the 1917 revolution, ending up a penniless exile in Nice. She was surviving precariously on nothing but her pride, her resourcefulness and her unbudgeable will when, in 1932, she found temporary work, first as a studio assistant, then as a domestic, with Matisse and his wife. It was not for another three years that the painter asked her to sit for him. Lydia was 25, Matisse was 65. She thought of him as a kindly and polite old gentleman because (unlike previous artists, who had taught her to detest modeling) he never pawed at her or tried to take off her clothes. "Gradually I began to adapt and feel less 'shackled,' " she wrote, "...in the end, I even began to take an interest in his work."

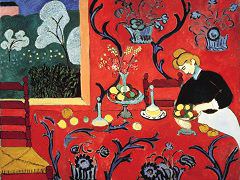

The first paintings Matisse made of Lydia combined the phenomenal virtuosity that had cost him so many years to perfect with his original instinctive ability to compose spontaneously in color. Matisse's son Pierre told his father that he had renewed himself as a painter with Pink Nude, for which Lydia modeled over a period of six months in 1935.

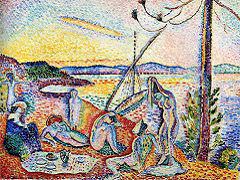

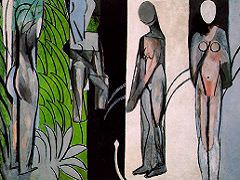

That autumn Lydia posed for a drawing of a nymph being wooed by a satyr, a theme Matisse had first painted some 30 years earlier, when, as she said herself, his handling was far more brutal than in the variation he did of her. "With me, he knew how to be gentle and seductive. He was charming, and so touching. He knew how to tame me." Matisse said he came eventually to know her face and body by heart, like the alphabet. The collaboration they established together gave Lydia a new sense of power and purpose. As she added the duties of studio manager to those of principal model, painting became the central core of her life as it was of Matisse's.

It was their working alliance, rather than any question of adultery, that precipitated a crisis in Matisse's marriage. Faced with an ultimatum from Amélie ("It's me or her"), Matisse chose his wife and sacked Lydia, but it was too late. Amélie, still furious over what she viewed as his betrayal, left her husband early in 1939. Lydia, returning briefly to help out in the studio in Paris, found herself trapped with Matisse in a stream of people fleeing invasion after the declaration of war with Germany. "A decision had to be made there," she said, "as to whether or not he was to take me with him." Matisse drew Lydia in her traveling hood at the start of the long journey they were about to make together through war-torn France. She remained at his side for the rest of his life.

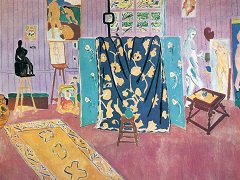

Visitors to Matisse's studio never tired of speculating about the role of the beautiful, enigmatic secretary known as "Mme Lydia," but few doubted that his survival depended on her, both as a man and an artist. In his closing decade in the face of exhaustion and failing health, Lydia made it possible for him to produce his final masterpieces - the chapel at Vence and the colored paper cutouts now generally agreed to be among the greatest inventions of the 20th century. Matisse died on November 3, 1954. He was 84. The day before, Lydia had come to his bedside with her newly washed hair wound in a towel turban, accentuating the classical severity and purity of the profile Matisse had so often drawn and painted. He sketched her with a ballpoint pen, holding the last drawing he ever made out at arm's length to assess its quality before pronouncing gravely, "It will do."